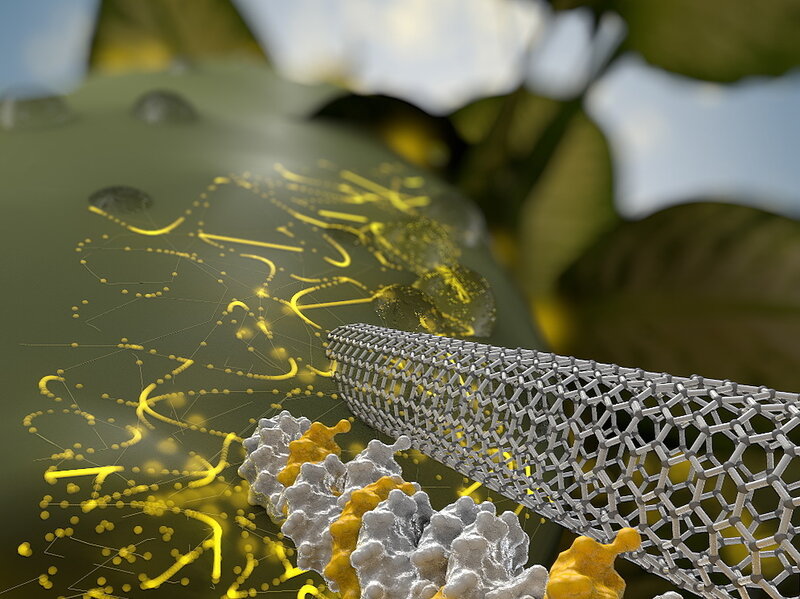

An artist's rendering shows a needle-like

carbon nanotube delivering DNA through the wall of a plant cell. It also may be

possible to use this method inject a gene editing tool called CRISPR to alter a

plant's characteristics for breeding.

Courtesy

of Markita del Carpio Landry

Is

there an efficient way to tinker with the genes of plants? Being able to do

that would make breeding new varieties of crop plants faster and easier, but

figuring out exactly how to do it

has stumped plant scientists for decades.

Now researchers may have cracked it.

Modifying the genetics of a plant requires getting DNA into its

cells. That's fairly easy to do with animal cells, but with plants it's a

different matter.

"Plants

have not just a cell membrane, but also a cell wall," says Markita Landry,

assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University

of California, Berkeley.

Both methods have limitations. Gene guns aren't very efficient,

and some plants are hard, if not impossible, to infect with bacteria.

UC Berkeley researchers have found a way to do it using

something called carbon nanotubes, long stiff tubes of carbon that are really

small. Landry came up with the idea, and the curious thing is she's neither a nanotechnology

engineer nor a plant biologist.

"I'm a physicist," Landry says. "When I started

my lab at Berkeley two years ago, my lab was focused exclusively on imaging

between cells."

Markita Landry, assistant professor of chemical

and biomolecular engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, came up

with the idea of using carbon nanotubes to get DNA into plant cells.

Courtesy

of Marcelo Perez del Carpio

She was planning to use carbon nanotubes as kind of external

scaffolding around the cells to make it easier to see what was going on between

them. "This was a project that failed pretty hard and pretty quick,

because instead of staying outside of the plant cells as we had presumed, these

nanotubes were going straight into the cells," Landry says.

So in the spirit of corporate management gurus, she turned a

problem into an opportunity.

"We flipped it around and made it a DNA delivery platform

instead," she says.

A strand of DNA is small enough to slip through the plant cell

wall, but it's not rigid enough. "You can kind of think of it like a

floppy string," Landry says. "If you try to push a floppy string

through a sponge, it's not really going to work, but if you take a solid needle

and try to push it through a sponge, that will work much better."

Attaching the DNA to the carbon nanotube gives you that

nano-needle.

But that DNA only affects the single cell and lasts for just a

few days before it degrades. To make a permanent change, you need to affect the

plant's genome using a gene editing tool such as as CRISPR.

Landry says it also might be possible to use nanotubes to

deliver CRISPR. Once inside a cell, from let's say an apple tree, CRISPR could,

for example, turn off a gene that causes browning in apples.

"We would end up with an apple tree whose apples don't go

brown when you cut into them," Landry says.

The

idea of using carbon nanotubes to get DNA into plant cells is intriguing to

some scientists, but "I think they've got a little ways to go to make it

really interesting," says Laura Bartley,

associate professor of plant biology at the University of Oklahoma.

Bartley

says it will be important to show that the method works in different varieties

of plants besides the two Landry describes in a recent paper in Nature Nanotechnology:arugula and wheat. But she's

impressed that the new approach appears to be able to get DNA into grass plants

such as wheat.

"If it works the way they think it does, I can imagine a

lot of people wanting to use that," Bartley says.

In fact, she says she's thinking about trying the invention in

her work on grass plants.

No comments:

Post a Comment